One bright, shining moment

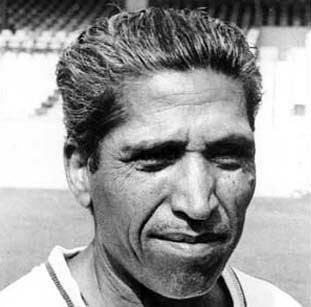

Twenty-four years ago after the Tokyo triumph, Shankar Laxman reflects on his life and the state of hockey in India today.

Twenty-four years ago after the Tokyo triumph, Shankar Laxman reflects on his life and the state of hockey in India today.

‘We had practiced very hard and the co-ordination in our team was something to behold. Before the tournament, I had made a firm resolve that I would not let the ball past me at any cost.’ Shankar Laxman was as good as his word. Effortlessly mowing down the opposition, India powered its way to its sixth successive Olympic hockey gold medal in Melbourne, in 1956. Beating Afghanistan 14-0, the US 16-0, Singapore 6-0, Pakistan 1-0. Not a single ball had got past its redoubtable goalkeeper.

Now, 55 years old and long since retired from active competition, Shankar Laxman recalls those heady days with justifiable pride. With the Olympics making the headlines again and India’s hopes of making a dent on the sporting scene looking grimmer than ever, it is with wonder that one looks back on a time when bagging at least one gold was virtual certainty.

One of the finest hockey goalkeepers the country has produced, Shankar Laxman ironically landed his first job due to his expertise in football. ”I was a reasonably good player,” he recalls, ”good enough to have been selected as a sepoy in the army on the basis of my game.” He gave up studying beyond the Higher Secondary in order to join the army.

It was the strict army habit of obeying orders unquestioningly that was responsible for getting him to change his game. ”In our team there was a Major Sanwal Singh, a keen sportsman. Some time in 1951-52, he began observing my game closely. He noted that I was equally at ease playing with both my feet. He told me that I would make a good hockey goalkeeper. I was scared to play hockey- especially as a goalkeeper! But in the army, orders are orders and they have to be obeyed.”

What helped to reconcile him to the switch was the enormous popularity that hockey enjoyed in the country at the time.

He almost made it into the inter-command hockey tournament in 1954. To get this far meant going through a lengthy selection process through all the various levels of qualification. But at the final stage the selectors felt that Laxman was too young and inexperienced to qualify.

Not a bit put off, the young goalie redoubled his efforts and in 1955 was selected as the goalkeeper of the formidable Services team for the Nationals at Madras. It was here that he met the man he calls his guru. ”Francis had represented India in the two previous Olympics as goalkeeper. He was quite impressed by my game and was certain that I would make it big one day. He was always a great inspiration to me, ” says Laxman gratefully.

The same year saw Laxman’s first international exposure. The Indian team was to play in the world hockey festival in Poland. Laxman was selected as the second goalkeeper, the first being Francis. Though Francis played in the festival in Poland; for the tour of Sweden, Germany, and Holland that followed, Laxman was allowed to try his wings, and turned in a very impressive performance.

There was another win for the Services at the nationals in Jalandhar the following year, with Laxman guarding the goal. And then the big Event, The 1956 Olympics at Melbourne. The selections for The Olympic team were held in Dehradun. Laxman was chosen to be the first goalkeeper, Francis, number two.

The Indian team had won the gold in the five previous Olympics, demonstrating their complete mastery of the game. Under Balbir Singh senior, they pulled off their sixth victory at Melbourne without conceding a single goal, an incredible achievement in itself.

After this heady victory, came a succession of disappointments: India lost to traditional rivals Pakistan at the Asian Games in Tokyo, in 1958. And then came the disappointment of losing the 1960 Olympics at Rome. ” In the Rome Olympics, we lost to Pakistan by a solitary goal in the final. Our unbroken gold-winning spree was halted by what was a stroke of bad luck. ” The game is clearly etched in Laxman’s mind. ”Our team played well, ” he says. ”We were continually on the attack, but unfortunately missed nearly a dozen easy chances. In what was only one of the few occasions that Pakistan could make a move, their left-in managed to dribble past our defenders. I went to intercept him at the top of the D, but just a split second before, he scooped the ball over my head. The agony of that goal and our defeat was enhanced because that day we had played very well.”

The final score at the Asian Games in Jakarta, in 1962, also stood in favor of Pakistan. With the political situation between India and Pakistan being particularly tense at the time, security for the final match between the two countries was tight. ”In such a tense environment we just could not perform well, ” Laxman recalls.

In Tokyo, in 1964, India got the chance to reassert its dominance. The Tokyo Olympics was Laxman’s last appearance at this sporting extravaganza. And it proved to be memorable one. ”Although all my team-mates played well, the crowds liked my game a lot. From the goalpost to the victory stand, I was on the shoulders of admirers-the response and ovation we got was overwhelming. To me the final of the 1964 Olympics was the most memorable of my career, ” says an elated Laxman, recalling even at this distance in time the exultation of that victory.

As one intimately connected with Indian hockey in its heyday, Laxman is eminently qualified to judge the difference in performance then and now. ”We performed well as long as the game was played on grass or turf. Indian players were skilful with their sticks and at short passes because they have very supple and flexible wrists, unlike the Europeans. The European coup of the hockey field began with the artificial surfaces they introduced, which require a lot more stamina on the part of the player; and when it comes to stamina and nourishment we stand nowhere in comparison to them.

”Then, the rules have changed so much, that now, the ball is more in the air than on the ground, to facilitate the long passes the Europeans prefer. We took a long time to adapt to these changes and in the meantime we were overtaken.”

But in 1966, Indian hockey was still a power to reckon with. That year, at the Asian Games in Bangkok, Laxman was appointed captain of the team. ”I told Ashwini Kumar of the IHF that, as such, I had no desire to become captain, but since the IHF had appointed me, I would like a few conditions to be observed. One was that there should be strict discipline in the team and any breach of discipline should be strictly dealt with. To me, discipline is the prime difference between a winning combination and a losing one. Even a mediocre team which is disciplined and co-ordinated can stage an upset or two. Second, once the team is on the ground, all players shall be their own captains.”

This policy payed off. Under Laxman, India achieved the rare honour of winning the hockey gold at the Asiad for the first time, in 1966, beating Pakistan in the final.

Laxman made his last tour of Europe in 1967. Though he was still the best custodian of the Indian goal and in good shape physically, he decided to call it a day. When he retired from competitive hockey, Laxman had attained the rank of subedar in the army. When he retired from the army in 1979, he was a captain.

In recognition of his services of the game the Arjuna Award was conferred on him in 1964 and the Padma Shri in 1967. He was also awarded the Yeshwant Singh Trophy by the army and three international hockey diplomas in 1956, 1964 and 1966.

The army authorities helped him to set up a shop in Mhow, his hometown, where he lived now. But running a shop was not an occupation he found congenial, so he gave it up and today leads a quiet, contented life. ”I go for walks in the morning and play tennis in the evening to keep myself fit,” he says. ”I also love helping youngsters improve their game-giving them tips to help them play better. I am also a member of various sports committees and am appalled at the poor standards and facilities that prevail.”

Which brings us to the million-dollar question: is there any way India can regain her eminence in the world of hockey?

Yes, says the veteran hockey player, ”but it won’t be a cakewalk. We have to start at the grass-roots level, popularise the game, search for budding talent, then ensure proper coaching and guidance. Second, we must revert to our old style of 5-3-2-1 instead of the present 4-4-2-1. The latter set-up is effective only when a half can also function as a forward but our players do not have that much stamina. So, in our case, it becomes a defensive pattern aimed at drawing the game, whereas the motive must be to attack, score and win. All this will take time and patience. But the resurrection of our so-called national game is definitely a worthy cause.”

Wouldn’t the country benefit by using the services of the two-times Olympic gold medalist instead of pensioning him off? Laxman had received two lucrative offers to coach at Narsinghpur and Bhilai, but he turned them both down. After being away from his family for such long stretches of time, he would now like to be with them more. One might expect life in retirement to be pretty tame for a man who has stood thrice on the winner’s podium in the Olympics and Asian Games, the approving roars of the crowd ringing in his ears. But as he sits in his room with photographs and citations lining the walls, his calm, composed demeanor denotes a man at peace with himself, content at a job done and done supremely well.

Show Pagination

Show Pagination